Dozens of post-it-notes mark the pages of my copy of Lawson’s book, reminding me about details of Morphy’s life. Reviewing this book by telling how great it is won’t do. Comparing the differences in chess culture in the 1800s versus now is better. I won’t be sharing everything; just enough for you to understand why this book is worth reading cover to cover.

But, yea, it was a really great book!

Cheating in Chess during the 1800s

GM Igors Rausis, caught cheating with an embarrassing photo we have all seen by now (here is the chess24 article), reminds us some people are willing to steal success. In the past 2-years, there have also been some fairly high profile cases of cheating: coach coercion of students, adult-team sandbagging, and hiding a cellphone in a bathroom stall under toilet paper come to mind. Lawson’s book showed me the that cheaters plagued chess in the 1800s. It got me wondering how does a person cheat in the 1800s? I later realized I should have began with “Why do people cheat?”

The motivation to cheat has always been the same: to gain a tangible benefit to elevate a person while bypassing genuine improvement practices. Today, those benefits might include prize money, titles, invites to tournaments, or rating increases for various purposes. In the 1800s, there were no titles, ratings, and chess events were rare outside of club and match play. Though, occasionally, there were stakes.

However, there was reputation. The chess world back then was smaller. The main designation of prestige and prowess was reputation. Print publications underscored the prize of reputation by publishing games much more often than today’s media. Thus, one’s repeatedly good results against highly reputed players always led to prestige thanks to newspapers. This reputation-as-a-prize argument is further evidenced by the life Morphy led throughout Europe and New York. Always invited to soirees, royal events, and political events, Morphy made friends in the highest places throughout Europe.

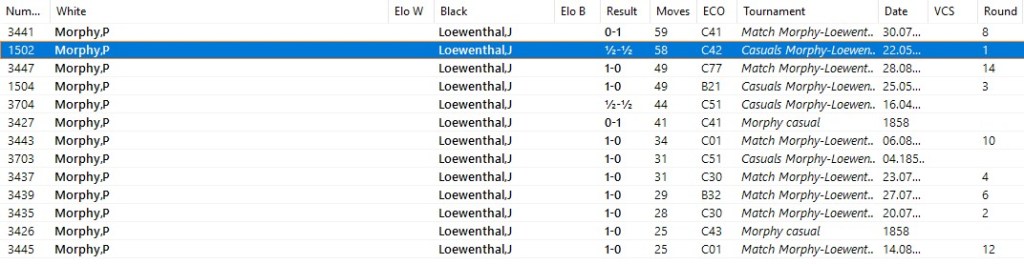

Johann Jacob Loewenthal was the first prominent player to meet Morphy. The meeting took place in New Orleans when Morphy was only 12 or 13 years old. Earning 0.5 out of 3.0 against Morphy (the first child prodigy?? not sure on that…), Loewenthal’s ego couldn’t handle it. To protect his reputation, he devised a devilish plan: publish a book with Morphy’s games but change the moves to one of the games to end the game in a draw instead of a loss. Then, encourage future authors to use his work which propagated the lie in many future publications.

Well, Loewenthal’s plan worked. Right now, in ChessBase 15, the most current version of ChessBase as of the publication of this article, this game is listed as a draw when Morphy actually won:

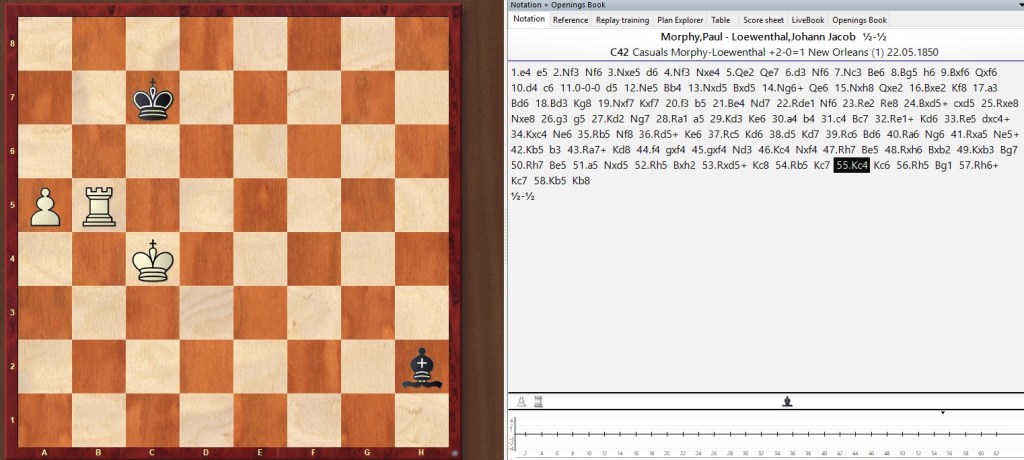

The game actually finished at move with 55.Kc4. You can play through the game here. Be sure you’re viewing the proper game by clicking the correct “chapter” on the left side of the board; also, see the note in the notation at move 55. The following position is where the game ended but you can see the notation trails on:

Made aware of this issue at some point, Moprhy chose not to publicly dispute it. Loewenthal and Morphy actually became friends. Paul always chose to look past this transgression as it was of little consequence. After their match, later on, Morphy used his winnings to furnish Loewenthal’s apartment at a cost of around £120. While there may be no love loss; I’d still like to see the record set straight.

A different form of cheating…

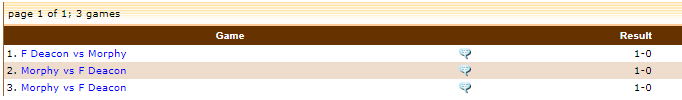

More strangely, a man named Deacon made a very public claim that he had played Morphy. All 3 games were published in the most widely available chess column written by none other than Howard Staunton. Chessgames.com actually has these games listed (see picture below or link above); however, the comments denote everyone is aware these games were not actually Morphy games (the games are not in ChessBase 15).

The alleged score was 2-1, Morphy ahead. Morphy denied this with a soft but firm hand. Morphy may have been in the same room as Deacon at some point in Europe; however, they never played a 3-game match. Called forth by Deacon, the only witness to this match never addressed the authenticity of the match but stated how outrageous everything is becoming (he was also a relative to Deacon).

Of the 3-games, one was spoken for by someone else, a friend of Morphy’s, claiming he played the game and not Morphy. The others likely had similar stories but were never determined. Deacon made claims against other players, too. Most notably, Steinitz, who rebuked Deacon’s claims more forcefully than Morphy. Interestingly, when these Deacon claims were being made in the early to mid 1860s, an anonymous American, who was in London, stated in a letter to a newspaper that “the cause of chess was injured by the constant controversies and bad deeds of chess players.” I find this is often true today with petty rivalries dotting the chess landscape.

It would seem the way to cheat in the 1800s is to make up or alter games. Then, have them featured in various chess publications across Europe and the US. It is an interesting concept because the cheater is, essentially, trying to damage the other player’s reputation to protect their ego. It is far more damaging to undermine another’s reputation than it is to deal with one’s own assaulted ego.

Back then, protecting one’s ego sometimes meant fire and brimstone to the bitter end. Learning how to lose is a critical skill in chess that many never learn.

Good Sports and Poor Sports (but not cheaters)

On page 75 of the hardback edition published in 1976, Paulsen gives a speech thanking Morphy for handing him an award: second place in the first Chess Congress held in New York. While Morphy had better results, Paulsen was extremely kind about losing. Because chess can be so contentious, Paulsen’s comments stood out to me:

“The honor which you have deigned to confer on me, in presenting to me such a beautiful and valuable present, is so great, that I only regret not being able to return my thanks in words sufficiently expressive of the feelings of gratitude, appreciation, and pleasure, which move my heart at this moment.”

In an increasingly divisive world, it is so nice to read such a statement. How great would the world be if we celebrated victories of others in the way of Paulsen? This is one way Paulsen kept a good reputation, in my opinion. There were many others who gave Morphy kind words when faced with their own demise. It was nice reading each speech given and each letter written to this effect.

But, I am not romanticizing the 1800s. Not everyone was as gracious as Paulsen in defeat – I am separating out the cheaters from the sore losers. It is explained that Morphy entered a match with a Mr. Stanley. Once the match score was Morphy 4, Stanley 0, and a single draw, where the winner must reach 5 victories, Stanley decided to resign the match through his second as opposed to showing up in person to do it himself. There are more rude ways to resign; but, I thought it was interesting his own hand wouldn’t tip the king.

Philip Sergeant, author of Morphy’s Games of Chess, highlighted an old custom chess players had as far back as the early 1800s related to this idea of poor sports: “The irritating custom of suppressing the players’ names or at best veiling them, has to be borne with; amateurs were very shy of their names appearing in print.” Obviously, many players didn’t want the public to have access to their losses. Reputation was everything. Having your poorly played games spread all over the world was an embarrassing result. In modern times, when a high level player plays a game, their game is streamed, relayed, broadcast, and written about as they make it. Top players no longer have the luxury to hide.

In Kentucky, years ago, I studied the online games of most of KY’s prominent players at the time. Being lower rated, I started scoring unexpectedly very well, and shot up past 2000 from 1700 – 1800. Once they found out what happened, Kentucky players digitally isolated themselves. To this day, none of them share their online screen names. This practice is not unique to Kentucky; however, I do take full credit for what happened in Kentucky. 😀

Regardless, I’ve come to believe hiding one’s online account, or obfuscating names from publications in the 1800s, as Sergeant stated, is a clear sign of weakness. Top players cannot hide their games and must always be updating their repertoire. Hiding one’s games in modern times is more about laziness, and not wanting to keep your knowledge current as often as is needed to stay on top, while hiding your name in the 1800s seems to be more about reputation.

The 1800s Ranking System

There was no numeric ranking system like Arpad Elo’s system introduced in 1960. There was also no formal ranking system. But, in reading Lawson’s book, there were a few different terms used which created a reputation-based hierarchy of chess players that was tacitly accepted by many based on how they spoke back then:

- Professionals

- Public Players

- Amateurs

- Private Players

Professionals played for stakes. Morphy was against doing this personally and refused all stakes given to him or found ways, when forced upon him, to give the stakes back. By the times, he was not considered a professional and didn’t like the insinuation when made.

Public players, which Morphy considered himself, were people who didn’t seem to mind if their games were published. They were willing to risk their reputations on publication if it were to occur – it was a form of risk making the games more meaningful. There is some cross-over between public players and amateurs; however, one key difference is public players generally were more famous than amateurs because their games were out in the world. Not all professionals enjoyed their games being published; therefore, not all professionals would have been public players in the strictest sense.

Amateurs were generally considered good players who didn’t seek to have their games published but weren’t as good as professionals or public players. When their games were published, they were often the losers of the games. They were never paid, though, for their games and they didn’t generally play for stakes. Most amateurs were club-based players who didn’t travel outside of their city very much – at least that is my impression.

Private Players were people who would only play behind closed doors. These people are responsible for name obfuscations and requiring opponents never to release game scores. Morphy had a habit of making certain people act like private players. I suspect it was this class of players who were most likely to cheat-through-publication.

While this is not a formal codified hierarchy, it is apparent in reading through Lawson’s book players referred to one another this way. During the end of Morphy’s life, he quit playing chess. While Morphy was still alive in New Orleans, his friend Maurian was considered “The best public-player in New Orleans” strongly suggesting Morphy was lower on the reputation hierarchy than he used to be; though, no one doubted his strength just his commitment to chess.

Paul Morphy’s Violet Eyes

The strangest detail of Morphy’s life is in Paul Morphy Seen Through A Lady’s Eye Glass, which was an article that ran in the Philadelphia Item in May of 1859. Here is the lady’s claim:

“[Morphy’s] large violet eyes, however, are the most noticeable feature in his face, with their long black lashes, and luminous iris, that seem to dilate, and grow larger every second.”

I never considered someone might have purple or violet eyes. Albinism came to mind since Morphy had such fair skin; but, his dark hair upended that short lived thought. The author of that quote goes into great detail about his eyes. I found it strange. Lawson pays no special attention to the comment and no one else elaborated on it that I’ve seen. Lawson couldn’t have corroborated it, so I am not hurling blame. But I needed answers; so, I went to google. I discovered “Alexandria’s Genesis,” which seemed to describe the violet eye thing. It turns out, though, it is an internet myth beginning in 2005 (here is my source). Here is the description from Snopes.com:

While we’d like to think of Morphy’s playing ability as superhuman, he clearly didn’t live 150 years, his health declined rapidly near the end, and he had a full head of hair. Conspiracies can be fun, but this didn’t quite fit the bill.

Eventually my google fu brought me to the actress, Elizabeth Taylor. She was known for her purple eyes. She often accentuated her eyes using purple eye shadow, clothing, and accessories.

In truth, she had very blue eyes. While we may see purple or violet, on a scientific level, they were blue. Uniquely blue, yes, but not literally violet or purple.

If Paul had eyes this color, it was likely similar to Elizabeth Taylor. Being such a rare eye color, it strikes me that no one else brought it up. Many people give descriptions of Morphy in Lawson’s book at various points – back then photos were more rare so descriptions of others were commonplace. It is entirely possible the woman who wrote the article perceived his eye color incorrectly. I doubt she would have fabricated it. Who benefits from falsely describing someone’s eye color? I dunno… maybe this one is lost to the wind…

Morphy vs Loewenthal and the Ownership of Games

Well after their first meeting in New Orleans, Morphy challenged Loewenthal to a match in Europe, which was accepted. The match’s stipulations, as laid out by Loewenthal, were very interesting. Morphy acquiesced to all of Loewenthal’s requirements:

- The winner of the first 9 games is entitled to the stakes.

- The first move shall be decided by lot and it will alternate from there.

- Half of the games were to take place at St George’s Chess Club and the other half at the London Chess Club.

- Play will take place on Mondays, Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays.

- Failing to appear within a half-hour incurs a 1-pound 1-shilling penalty; within an hour 2-pounds 2-shillings; hour and a half 5-pounds 5-shillings; to be payable to the opposite party.

- No game will go beyond one sitting unless adjourned by mutual consent.

- After 5-hours of play, either party can adjourn for an hour.

- The games shall be the property of the players.

If you read Bobby Fischer goes to War, Karpov on Karpov, and Unlimited Challenge, in that order, you will get a full outline, and timeline, of the negotiations between Fischer-Spassky and Kasparov-Karpov. While those negotiations were super intense, they looked nothing like the negotiations of Morphy and Lowenthal. You can see how times have changed (the list below is respective to the above list):

- Stakes are often divided, put up by FIDE, and 12 games are played at the WC level.

- When each player gets white and black is on a schedule and randomly decided.

- The games take place in a single venue.

- Scheduling rest days is indeed still done at the WC level.

- Being late in normal tournaments is quite regular with only a time penalty (or forfeiture); being late in a WC can result in a forfeit.

- Adjournments are no longer done.

- Again, adjournments are no longer a thing.

- The games are property of the organizers.

This is especially true for “8. The games shall be the property of the players.” Challenged so often over the years, there are now formal tournament rules which state organizers of events own game scores. If players could copyright their own games, and thereby copyright / patent their own moves, they could prohibit other players from using their moves. In essence, that would destroy chess as it would outlaw emulation of good moves. In the 1800s, if the organizers were the players, then they would still have the rights to the games even by today’s standards.

In 2016, this rule was challenged the day before the World Championship. The lawsuit alleged it was wrong for websites like chess24.com relaying moves outside of the paid-for streaming service (source). The websites who were relaying moves to their streams won the lawsuit (source). Thus, companies who pay for the rights to stream the World Championship cannot prevent third parties from watching their stream and relaying moves because no one can own, permanently or temporarily, a chess move.

I’d say this is one of the biggest differences between the 1800s and now within chess culture. The world is better for it because we can enjoy games of top players without having to worry about them being suppressed. It is also motivating for top players to remain in good form lest they lose their place among the stars through complacency.

The Morphy Coin

Not being a numismatist, I still found myself interested in the coin Morphy received after his match with Harrwitz and leaving Europe. I think it is one of the greatest trophies ever given to someone for a chess feat (here is the coin). It reads

“He has beaten Harrwitz in chess playing and Staunton in courtesy.”

What most people know is Staunton refused to play Morphy in a match. What I’d wager is less known is Staunton used his chess column to defame Morphy. Regularly misquoting Morphy, or failing to quote him at all, Staunton would publish letters from readers who were writing in to criticize something Morphy said. It is generally agreed upon that Staunton authored these letters himself.

Most people believe these two never played because a match never happened. However, there is one consultation game with Morphy and Barnes as white and Owen and Staunton as black. You can see the game here. Morphy’s side won convincingly (and Owen was no chump back then). According the Lawson’s book and research, it is more than likely Staunton and Morphy played games, behind closed doors, that same evening as the consultation game, without seconds. It is even stated that if games did happen, Staunton would have been very much against their publication. There is plenty of evidence to suggest Staunton would have stamped his feet at their publication. If these games did occur, Morphy truly did beat Staunton in courtesy by never saying a word.

Paul Morphy, the “first” World Champion

I think a common self-criticism in today’s chess world is, regardless of your rating or strength of play, you never quite feel strong enough. As a National Master whose been working toward Expert in my last few events, I can say I must agree I never quite feel strong enough. Even the current World Champion, Magnus Carlsen, feels he isn’t good enough at times. I think this is a universal feeling for chess players.

Morphy also agreed with this sentiment. Upon his return from Europe, where he threw down the gauntlet, beat everyone, challenging Coward Staunton, and declared he’d give anyone in the world pawn and move odds, he stated “[I] had not done so well as I should have.”

But, I believe Lawson had a secret wish. He wanted to set the record straight. His wish? Paul Morphy would be recognized as the official first world champion. His proof is substantial toward this claim and I agree with him. I’ll note before reading this book, I didn’t agree. I always felt that since the official world championship began with Steinitz v Zukertort that Steinitz was the first world champion. However, Lawson points out some interesting criteria regarding Morphy being first.

Because of Morphy’s success, many dinners were held in his name after matches and events. At least four of these events had speeches declaring Morphy World Champion. No one challenged the claim. Morphy was also called World Champion in both hemispheres. I would add that when Morphy went to Cuba, and was called World Champion, his reputation preceded him as he went incognito while fleeing the Civil War, to go to France, but was discovered a few days in.

Lawson also put forward Steinitz was World Champion because he and Zukertort agreed it would be so. I mean, if you want to get down to it, I am the World Champion Zombie Chess and Ghost Chess player. Why? Because I invented both of those variants, I have defeated my opponents in the various WCs we held. I have also defeated a GM blindfolded in ghost chess, and several IMs and a Master, too. But, does this really make me World Champion simply because I say so and all the opponents agreed it was for the WC title?

Steinitz was a legitimate WC who held the title for 28 years. He more than earned it; however, I think his claim of being first WC is not legitimate in light of Lawson’s reasonable arguments. James H. Gelo writes in the preface of his Chess World Championships: All the Games, 1834-1984 that there were 3 periods of World Championships:

- The period from 1834 – 1865 which was before official WCs

- 1886 through 1947 where people competed for the titled

- 1948 through present when FIDE was established

Gelo states Morphy was not technically a World Champion but Lawson’s case is much more thorough and convincing. If we go by the periods established by Gelo, then Morphy would be the 5th World Champion and Labourdonnais would be the first. However, Morphy was the first to actively seek out as many strong opponents as possible – I think that matters.

Morphy truly was the Pride and Sorrow of chess. When listening to this song by Ludovico Einaudi, I think of Morphy. It is a melancholy song that celebrates the once great Arctic that is now melting away – a metaphor for the great Morphy who slowly withdrew from meaningful chess.

My final point I wish to make about Morphy is at the 2019 US Open in Orlando, Florida, I heard GM John Fedorowicz state, at the Senior Tournament of Champions award ceremony, that he gets “yelled at” by lower rated players, when he says Morphy was only rated about 2000. While I agree Morphy is no 2800, I don’t know any 2000 rated players who regularly play 8 blindfold games against the strongest players they can find. 🙂

Bobby Fischer wanted players to to copyright games and be able to economically benefit from their publication or dissemination through applicable media. It was ruled out . Chess games belong to us all. They don’t qualify as intellectual property, and likely never will.

LikeLike

Any chances “violet eyes” could be referring to the violet flower?

LikeLike

She was describing him from the head down if I recall. I think she meant his eyes; however, if the term “violet eyes” refers to flowers, that is new to me – perhaps?

LikeLike

Chess games as intelkectual property would break from all precedent. It is a serious game, and top professionals and a few others may earn a living from it. But in the end, it remains a game, and the sum of its moves don’t require the technological innovation protections necessary for competitive commerce.

LikeLike